תנועת הבינה

תנועת הבינה

תמר ברניצקי / יאיר ברק / הדר גד / יונתן הירשפלד / רותי הלביץ כהן / עמרי הרמלין / נאוה הראל-שושני / דרורה וייצמן / גבי זלצמן / דליה זרחיה / רוני יפה / דנה מנור כהן / חיימי פניכל / נעה רז מלמד / שיר שבדרון / ליאור שור / מיכל שכנאי

אוצרת: רותם ריטוב

17.10.25 - 03.01.26

תנועת הבינה, תערוכה מספר 51, התערוכה האחרונה

מציגות ומציגים: תמר ברניצקי, יאיר ברק, הדר גד, יונתן הירשפלד, רותי הלביץ כהן, נאוה הראל-שושני, עמרי הרמלין, דרורה ויצמן, גבי זלצמן, דליה זרחיה, רוני יפה, דנה מנור כהן, חיימי פניכל, נעה רז מלמד,שיר שבדרון, ליאור שור, מיכל שכנאי

אוצרת: רותם ריטוב

התערוכה האחרונה נושאת משקל אחר. כמו אחרית דבר או מכתב פרידה, מוטלת עליה איזו אחריות סמויה לחתום את הדברים. זהו משקל הסיכום, שבו טמונים מסרים ותובנות בעלי משמעות ותקווה כלפי מה שהיה, כלפי העתיד ובעיקר כלפי הריק שיוותר.

על התערוכה הזאת עבדתי לאט מהרגיל. כמו דחיתי את הקץ. באותה העת הלך והתגבש גם ספר המסכם את פעילות הגלריה מאז נוסדה, והשקתו מתוכננת להתקיים במהלך התערוכה.

מלאכת הכנת הספר הציתה את ההשראה לרעיון התערוכה! הרי ספר מסמן היטב את המהלך השלם: התחלה, אמצע, סוף. זהו אובייקט מיוחד המתעלה מעל החומר, הנפח או הפונקציה שלו. הוא נושא בתוכו מאוצרות הרוח, ידע, דמיון ונדבכים של תרבות. השפעותיו נטמעות ברוחנו הרחק מעבר לנוכחותו הפיזית.

והנה, אנחנו ניצבים בסיפהּ של מהפכת הידע מהגדולות שידעה האנושות. רק לפני כ־100 שנים, בתחילת המאה ה־20, רוב אזרחי העולם לא ידעו קרוא וכתוב, ועל האזרחיות אף נאסר לדעת. מאז, הלכה האנאלפבתיות ופחתה עד שכמעט נעלמה מן העולם. בעבר הלא רחוק, מקורות הידע היו אנציקלופדיות, ספרות, מילונים ומגדירים. ספרים נכתבו ונערכו, הודפסו ונכרכו בקפידה ובעמלנות, ואף ניתנו בהוד והדר כמתנות לאירועים חשובים בחיים. הספר סימל מעמד, השכלה, רוח ואמונה בכתוב. אולם מהפכת האינטרנט שינתה את סדרי העולם, ומדפים עמוסי כרכים כבדים של האנציקלופדיה העברית[1] נושאים כעת מסכי פלזמה. ובתוך מהפכת הפצת המידע, הבינה המלאכותית פותחת פתח לידע וליצירה בעוצמה ובעומק שלא נודעו מעולם ומשנה את הדרך שבה אנחנו חושבים ויוצרים.

אך אל החופש היצירתי ואל המגע עם ידע בלתי נדלה נלווית גם אי־ודאות גדולה: האמת הפכה למתעתעת, נזילה, לא מוחלטת, והאנושות ניצבת בפני אתגר חדש: לעמוד על משמר האמת, להבחין בין בדיה לעובדה, בין מקור אמין לכוזב. הבינה נאבקת על עוגניה.

בתערוכה "תנועת הבינה" נוכחות רוחותיהן של דמויות רבות – מרות המואביה, מולייר, ג'ורג' גרוס, ישעיהו ליבוביץ' וירג'יניה וולף ועד אמנים יהודים שנספו בשואה וכורכי ספרים לדורותיהם ששמם לא נודע. קיומן הנצחי נובע מהסיפורים שעברו מדור לדור, מהמילה הכתובה, מהתרחבות הידע ומערכי הלמדנות, היצירה והמחקר. הרוחות מגיחות מתוך עבודות האמנות המוצגות, ובכך מתחבר דור האמניות והאמנים העכשווי לרצף הרב־דורי של תנועת הבינה. יש להוקיר את האפשרות לקחת חלק, גם אם צנוע, בהתגלגלות הידע האנושי.

יאיר ברק

עבודותיו של יאיר ברק בתערוכה הן חלק מתת־סדרה בגוף העבודות Regarding History. הן נוצרו ב־2008 במהלך תוכנית מאסטר בבארד (Bard College) , ניו־יורק, והוצגו מאז בווריאציות שונות. שם, בניו־יורק, כשהיה אורח בתרבות שונה, בארץ אחרת, ופעל בנוף זר, הוא ביקש להמשיך ולהעמיק בשאלות ובנושאים של זהות, זרות ומקומיות שעסק בהן עוד במרחב הישראלי.

במהלך העבודה על Regarding History, נחשף ברק בספריות הקולג' המרשימות לאוספים העשירים של ספרי "היסטוריה של הטבע", הכרוכים בעבודת יד בבד ובפשתן, כפי שהיה נהוג בתעשיית ייצור הספרים במחצית המאה ה־20. ברק: "התאהבתי בחומריות ובאופן שהיא מספרת היסטוריה. לא התייחסתי לתוכן הספרים, אלא לאופני הייצוג, הסמלים והטיפוגרפיה. סקרנה אותי המחשבה על אסתטיקה מצד אחד ועל איך מספרים היסטוריה מצד שני". הספרים בעבודותיו מתפקדים כייצוג ארכיטיפי לתשתית תרבות המערב וכאידיאה מופשטת, כמושג. הספרים מוצבים בקומפוזיציות המתכתבות עם מושגי היסוד של האדריכלות הקלאסית (שער, מדרגות) מתוך המחשבה על טקסט כסטרוקטורה וכאבן בניין בתרבות המערבית. העבודות נוצרו בטכניקת פקשוט packshot (צילום על רקע לבן נקי), אבל במקום מצלמה וסטודיו, הפך הסורק המשוכלל במעבדה הדיגיטלית של הקולג' למרחב העבודה.

הדר גד

ב־2019 הזמינה דרסי אלכסנדר, אוצרת המוזיאון היהודי בניו־יורק, את הדר גד להשתתף בפרויקט שעסק בביזת האמנות היהודית על ידי הנאצים. במהלך מחקרה של גד בארכיונים שונים, היא גילתה שמות רבים של אמנים ואמניות יהודים שנשלחו מפריז לאושוויץ. "למרות שמדובר באמנים ממקומות שונים באירופה, גיליתי שמספרי השילוח לאושוויץ עוקבים. רובם ככולם נשלחו יחדיו בקרונות הרכבת מפריז, כנראה אחרי שברחו אליה. הרגשתי צורך עמוק לתעד, ליצור מעין אנדרטה, ולהנציח שכבת תרבות שלמה ורחבה כל כך שנמחקה", אומרת הדר גד.

אקט ההנצחה נכנס אל ציורי הספרים - שמות האמנים רשומים על שדרות הספרים המצוירים: "זה כמו ציור טרויאני. כל שם הוא סמוי אך נוכח, והצופה מגלה את הסיפור דרך השמות". שם הסדרה "הפרעת זיכרון" שאול מהמסה של זיגמונד פרויד, שנכתבה כמכתב לחברו הסופר הצרפתי רומן רולן "הפרעת זיכרון על האקרופוליס",[2] בעת ביקורו באתונה. ורד לב כנען כותבת במאמר על פרויד כי במכתב זה שכתב בערוב ימיו, ב־1936 "עולים שני עניינים שונים הכרוכים זה בזה ושאת המכנה המשותף ביניהם ניתן לנסח בזיקתם למקורות התרבותיים והאינטלקטואליים של פרויד […] מחד גיסא זהותו היהודית […] ומאידך גיסא החינוך הקלָאסי שקיבל בגימנסיה, מתקבלת תמונת חיים שמעורבים בה כפילות, שניות וסתירות פנימיות […]. החזרה של פרויד אל שני המקורות המכוננים של זהותו המורכבת מתמקדת בקשר בין דמותו של אביו, יעקב פרויד, לבין דימוי נשגב המייצג את העת העתיקה, האקרופוליס. שני הסמלים, האב וההר, בהיותם סימנים מייצגים של עולם שהיה ואיננו עוד […]מהדהדים אצלו תחושת אובדן שמעוררת רצון להתבוננות פנימית […] מחשבותיו של פרויד על אביו המת ארוגות במחשבות על עולם שהיה תמיד עבורו בחזקת בית, אף שלא היה באמת שלו, אלא יותר בבחינת מקום הולדת נכסף".[3]

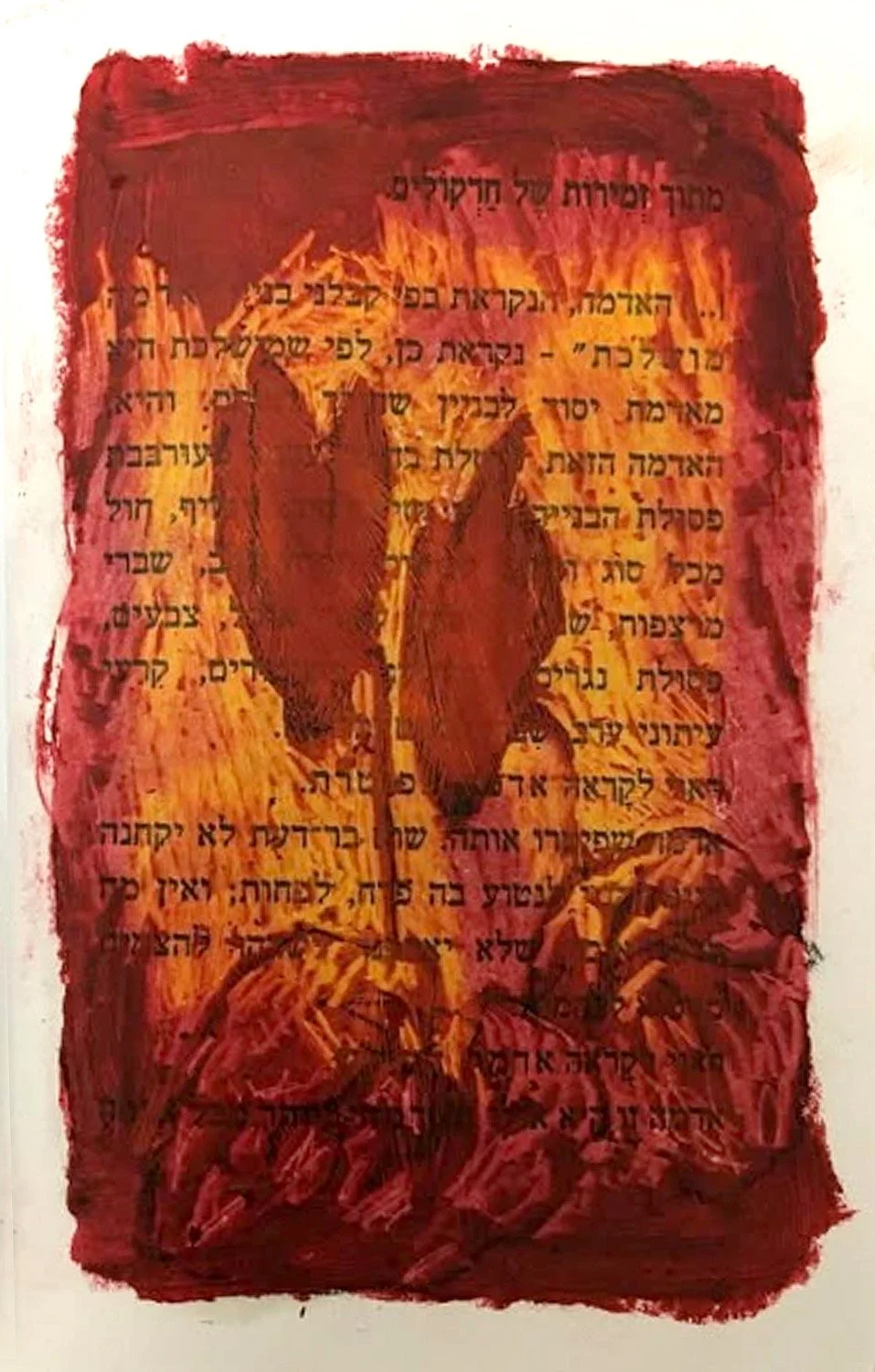

עבודה נוספת של הדר גד היא ציור הרקפות על גבי עמודים 7-6 בספרו של אבות ישורון, "רעם";[4] ציור יום־יומי בספרים ויומנים, אומרת גד, הממקד אותה ומניע תהליכי ציור.

גבי זלצמן ותמר ברניצקי

תהליך העבודה של גבי זלצמן ותמר ברניצקי מושתת על דיאלוג ושיתוף מלא בכל אחד משלבי היצירה. בעבודותיהם הם משלבים יחד אובייקט (ספר), חומר (טקסטיל), טקסט ודימוי גרפי, וחוזרים אל מחוות ידניות של מלאכות מסורתית: הדפסי רשת ותפירה חופשית במכונה. עבודותיהם רוויות רבדים ואזכורים, זיכרונות אישיים ונוסטלגיה. פס־הקול של ילדותם נתפר על ספריית הילדות מתקופת בית־הספר, רגע לפני שתיעלם. "אבי היה מורה דרך ואוסף ספריו הוא אוצר ילדות. אטלס כרטא הוא חלק ענק מילדותי. כשאבי שיתף בכוונתו לזרוק את הספרייה ואת האטלס, הרגשתי כמי שחייב להציל אותם ולשמר משהו מאותה התקופה. הטיפול בספרים הישנים משאיר אותם במרחב חי, קסום ורומנטי", מתאר זלצמן. וברניצקי מוסיפה: "פעולת תפירת האותיות הופכת את הזיכרון החולף למוחשי וברור. החוט השחור הופך מאמצעי חיבור לכלי איור, ואת הגעגוע לכדי חומר עכשווי". העבודות בתערוכה הן אך חלק קטן מיצירתם המשותפת. הספר משמש בה מצע קבוע, ונתפס בעבודותיהם כאובייקט ילדות נוסטלגי הזוכה לחיים חדשים להנכחתן של חוויות ילדות, אופטימיות והתפעמות מן הרגע.

יונתן הירשפלד

"שלוש סדרות קטנות ואחיות נולדו* לי מהמצב הנוכחי. כל חיי כצייר הסתייגתי מאמנות פוליטית, כיוונתי את ציוריי למחוזות יותר מטפיזיים, יותר נצחיים ואוניברסליים. חשבתי על עצמי כאמן שאינו פועל כתגובה למציאות אלא מתוך כור מחצבתו. אבל גודלו של אסון השבעה באוקטובר, הידרדרותה הרוחנית והמוסרית של ישראל, מלחמת הנצח ופירוקה של הדמוקרטיה הישראלית חדרו לסטודיו לבסוף. ניסיתי לשמר את הפעולה הציורית שלי, הפשטה, מודרניזם ישראלי ומבע ישיר, להביא את הפוליטי כרקע, כלא־מודע וכקבור מתחת. הכול שם בחוברת התחריטים הפוליטיים של ג׳ורג׳ גרוס,[5] התבהמות, פאשיזם, מלחמה – הכול. הנחתי עליהם את המחוות ההירשפלדיות הרגילות; להוציא פה ושם דגל ישראל, פה ושם כיתוב מתוך ירושלים של זהב. לבסוף, רכשתי לי ספר קודש, וחזרתי על הפעולה עליו: כי האמת היא שמתחת ללא־מודע הפוליטי, ישנו הלא־מודע הדתי". יונתן הירשפלד, 2025

* נולדו, כי הריתי, כי הפוליטי זיין אותי

רותי הלביץ כהן

במיצב "מגילת רות" ניגשת רותי הלביץ כהן אל הסיפור התנ"כי במבט אישי ואינטימי. היא מפרקת את הטקסט המקראי כדי לשוב ולקרוא אותו מחדש. היא בוחרת משפטי מפתח, מוחקת, מפרשת ומחברת, הופכת את המגילה למעין יומן אישי־נשי. בעבודת הווידאו שבמרכז המיצב נחשפת מגילת רות ועליה רישומים. הדפדוף האיטי וה"יד" המצביעה על הפסוקים, שיצרה האמנית, מלווים בשירה של שתי נשים, שני קולות: הראשון הוא קולה של הילה כהן צ’סלה, מורה לטעמי המקרא, והשני קולה של נעמי – בִּתה הצעירה של האמנית, החוזרת אחרי המורה. במחווה עדינה, פואטית וקולית זו נוצרת פעולה של חניכה בין־דורית, הממקמת את היחסים בין אם, בת ומורָה בתוך רצף של קולות נשיים המתעקשים להישמע בתוך עולם גברי.

כמו קהל, ניצבות דמויות אנדרוגניות גדולות־ממדים על הציורים התלויים, ספק פצועות, ספק חייתיות, עדוֹת לפעולת ההקראה. שבריריותן של הדמויות בציורים מסמלת את עוצמת הגוף הנשי אל מול המסורת, ומדגישה את התנועה בין פגיעוּת לנחישות. באמצעות ציור, רישום, וידאו וסאונד הלביץ כהן מטשטשת גבולות בין קודש וחול, בין חומר יום־יומי דל לטקסט קדום וקאנוני, ובונה מחדש מרחב נשי של טקסיות. מרחב שבו הסיפור המקראי הופך לכלי כתיבה על אהבה וכאב, פרידה והמשכיות, שבו הגוף והקול הנשיים נחרטים מחדש בהיסטוריה.

דרורה ויצמן

"קח ספר ופרוס אותו בסכין ובמזלג, עצום את העיניים ואכול ממנו: שולי הדף, כותר, חותם, טקסטורה של טקסט, שכבות של כריכה, עם קרטון ותחבושת ורשת סיבים לתמיכה, וסימנית בד מתפוררת. קח ספר והצל אותו מעברו, מעתידו ומגלגולו, מהשכחה, מערימת האשפה ומאחורי תיבת הגניזה".

דרורה ויצמן, מאי 2013

דרורה ויצמן יוצרת במרחב הדינמי שבין פירוק לשימור, בין טקס פרידה לאקט של בריאה. ספרים, נושאי ידע, הגות ותרבות, הופכים תחת ידיה לחומרי גלם טעונים בזיכרון אישי וקולקטיבי. בתהליך ידני ואינטימי, היא מפרקת אותם לגורמיהם: שדרות, כריכות, קפיטלים,[6] שולי דפים, חוטי תפירה, כתמים ומרקמים. את אלו היא שומרת, ממיינת ומרכיבה מחדש לכדי מבנים פיסוליים ומיצבים. עבודותיה מזמינות מבט איטי על חומריות הזמן, על שרידי עולמות חבויים. ויצמן מתבוננת בהם כשליחים ומלאכים, נושאי מסר אבוד, מחזירה אותם לחיים, אבל אחרים, באמצעות מחוות מוקפדות של סידור, הדבקה, חיבור והעמדה. היא מכנה את מרחב העבודה שלה "המשאבה" – מרחב קולט, סופג וממיין: "העבודה נעשית במטבח ובסלון, על השולחנות ועל השטיח, בכל שעות היממה בנוכחות מסך הטלוויזיה והחדשות הבוערות", כתבה ויצמן ב-2021.

תהליך עבודתה סדור:

ראשית, ניקוי חיצוני ולאחריו דפדוף ועיון, שמירת מילים ודימויים בעלי השראה.

השלב הבא הוא ניקוי פנימי: הוצאת כל התוכן. יש חשיבות לאופן תלישת הדפים – אחד אחד, במקבץ, במשיכה כלפי מטה או מעלה, לאט או מהר. לכל פעולה השפעה על המראה שיתקבל. כמובן שיש הבדל בין ספרים המודבקים בדבק, מחוברים בסיכות או תפורים בחוטים.

לאחר הניקוי נחשפת שדרת הספר ואחיזתה בכריכה משתחררת, כמו שמפלטים דג עד שמופיעה האִדרה. לכל שדרה חלוקה פנימית משלה המותאמת לחוטים ולתפרים שאוחזים בדפים ובהתאם לאופן ולכיוון הסרתם. לעיתים ויצמן רושמת בעיפרון את שם הספר לפני שזהותו תיעלם כליל.

טיפול בקפיטלים: אם אמרות הבד (המשמשות לחיזוק ולנוי בקצוות הספרים; צמודות לקצות השדרות) צמודות היטב, הן נשארות. אם לאו, הן מנוקות בנפרד, נגזרות מחוטים סוררים ונאספות אל קופסה.

טיפול בגב הספר: כשהכריכות, הקדמית והאחורית, מפורקות מאחיזתן, נותר גב הספר והמילים שעליו. סילוק כל המתקלף ואיחוי כל הקרוע והתלוש מותיר את הבחירה לטפל בצד החיצוני של הכריכה (לרוב בצבע אדום) הנושא מילים חרותות בכותר וייחוד כלשהו – פגם או מרקם מיוחד. הבחירה לטפל בצד הפנימי של הכריכה תוביל להמשך פעולת חשיפה וארכיאולוגיה בשכבות הקרטון.

לבסוף, בריאה מחדש: ישן אכול תולעת לצד חדש מהודר, נדוש עם נדיר, עולמות רחוקים מארצות ועמים טרם עידן המסכים, אבות ההשכלה ואימהֹות התרבות, זיכרונות בתי הורינו ותקומת הארץ, הנצחה בתכריך קטיפה, מלחמות ואמנות שניתן כיום למצוא בקלות ובאיכות גבוהה במרשתת.

בתערוכה "תנועת הבינה" מקימה ויצמן חזון ישן – ספרייה.

"לפעמים זה מתחיל במילים, את רק צריכה לגלות אותן למישהו וזה מתגלגל", דרורה ויצמן, 2025

נאוה הראל-שושני

בעבודה "עם הספר 2" מתיכה נאוה הראל-שושני שני סימבולים מוכרים זה אל תוך זה: האחד הוא דימוי של ספרים ניצבים על מדף, המייצג את הזיקה העמוקה של היהדות לספר, ללימוד, למילה הכתובה ולהגות; והשני הוא דימוי חומת ההפרדה, המייצג באופן הבוטה ביותר את הקונפליקט הישראלי־פלסטיני ואת ביטויו הפיזי במרחב הגיאוגרפי. יציקת הבטון על הספרים, כרכי אנציקלופדיה, הופכת אותם ממרחבי ידע לאנדרטה של מרחב מסוכסך. ברקע העבודה מביעה הראל-שושני את עמדתה: "הפכנו מעם נרדף לעם רודף".

הראל-שושני פועלת במרחב האמנות הארטיביסטי,[7] ועבודתה האמנותית מוקדשת לניסוח תגובה למציאות האקטואלית הישראלית, להבעת מחאה פוליטית ולהעלאת מודעות חברתית להיבטים שונים של הכיבוש ושל הסכסוך הישראלי-פלסטיני.

עמרי הרמלין

העבודה "נשימתה האחרונה של האמת" שייכת לסדרת פסלים ריאליסטיים של ספרים וספריות שיצר עמרי הרמלין במהלך השנה האחרונה. הסדרה עוסקת במקומה ומעמדה של האמת בעולם מתערער, וכל אובייקט־ספר בה מבטא מחשבה מתומצתת על התוכן המילולי המסתתר בין דפיו הבלתי ניתנים לדפדוף. יחד, העבודות מהוות מעין ארכיון פיסולי של תהיות על מהותה של האמת. הבחירה בספר ופיסולו באופן כה מציאותי מבטאים את הרצון לפענח את משמעות "הספר", המסמל באופן מסורתי את מקור האמת המוסכמת, את חוכמת החיים ואת הערך המוחלט, במיוחד בעידן העכשווי, שבו האמת הולכת ומתעמעמת מיום ליום. בעידן הפייקים והבינה המלאכותית, השאלה מה אמיתי או מי דובר אמת נעשית מהותית. שם העבודה מבטא את המתח בין האמת המוחלטת ובין הפרשנות האישית, בין ידע מהימן למציאות בדויה, בין עובדה לייצוג דהוי של נרטיב רגעי.

דליה זרחיה

רבות מיצירותיה של דליה זרחיה מבוססות על חפצים נושאי זיכרונות. נוכחות הרוח והעבר הטבועה בהם מהווה נקודת מוצא לתגובתה האמנותית ולמסע של גילוי ההיסטוריה החבויה בהם.

עבודות הספרים המוצגות בתערוכה הם רק חלק קטן מגוף עבודות רחב, שזרחיה עובדת עליו זה כשנתיים, מאז שתמי סואץ מסרה לידיה אוסף ספרים גדול, שהינו חלק מהאוסף הפרטי של עוזי אגסי, האספן, ההיסטוריון, מבקר האמנות, דפס־אמן, מו"ל ומייסד ההוצאה לאור "אבן חושן" ועורך כתב העת הספרותי "שבו". "אספתי את הספרים" אומרת זרחיה, "ומיד התחילו לעלות שצף של רעיונות. נכנסתי לאובססיה והתחלתי לאסוף ספרים, גם מהרחוב".

גוף עבודות הספרים הוא מחווה לאמנות עשיית הספרים ולמסורות המלאכה של בעלי המקצוע, הכורכים והדפסים. התפתחות הדפוס הטכנולוגי והנגשת הידע ברשת שינו את האופן שאנו מייצרים וצורכים תרבות. פרקטיקות מסורתיות נזנחו ונעלמו, ופינו את מקומן לייצור זול, זמין ומהיר. מעמדו של הספר כאובייקט וכסוכן תרבות דעך, ובחללו פועלים מאגרי המידע והידע הדיגיטליים, משנים את פני התרבות. זרחיה מבקשת לשמר את העבר, את הזיכרון, את ההיסטוריה.

רוני יפה

מסורת הציור הקלאסי משמשת את רוני יפה, שלמדה אותה בפירנצה, ככלי התבוננות על הישראליות. ייצוגי הטבע הדומם בציוריה הם אובייקטים המסמלים שכבות תרבות מקומית, ודרכם היא בוחנת את היחסים בין חומר לרוח, בין סדר לכאוס. נקודת המוצא בשני ציוריה בתערוכה הוא הביטוי המשנאי "אם אין קמח אין תורה",[8] הדן בזיקה ההדדית בין החומר, הצורך הקיומי, ובין חיי רוח. יפה מרחיבה את הביטוי מעבר למרחב המסורתי: קמח בהכשר בד"ץ לעומת קמח מיובא מאיטליה; התנ"ך לעומת ערמת ספרים בתחומי דעת שונים: פילוסופיה, פרוזה, מחקר, אבולוציה, קלאסיקות, מגדיר צמחים, שירה, ילדים ואטלס. ההבדל התרבותי בין העולם הדתי והחילוני מקבל ביטוי סמלי גם בקומפוזיציה: זו הנקייה, הברורה, השמרנית והסימטרית לעומת המבולגנת, המגוונת, המכילה מבחר שדות תרבות ודעת. במרחב החילוני מסתתרת סימניה צהובה בין הדפים, מהדהדת את המציאות העכשווית של החטופים, והופכת את הציור לזירה שבה נכרכות היסטוריה, תרבות ואקטואליה יחד.

דנה מנור כהן

הסטודיו של דנה מנור כהן עמוס ספרים ישנים, המונחים בערמות כמדפים. היא מציירת על כריכות ספרים שנבחרו בקפידה, מתוך כבוד למורשת שהן נושאות בחובן. "הספרים הללו היו פעם חשובים למישהו, ובכל פרט בהם הושקעו מחשבה ועמל. למצוא ספר ישן זה כמו למצוא אוצר. יש בו סוד. ספרים ישנים הם גשר בין עבר והווה, הם נושאים זיכרון, במיוחד אלו הישנים, הקרועים, שלעיתים התכסו בעובש ולפעמים יש עליהם הקדשות". מנור כהן מתארת את ההתרגשות שבהפיכתם למצע ציור. על הכריכות היא מציירת בטבע, במקומות שהיא אוהבת, חיה או מבקרת. פעולת הציור של "המקום" הנבחר היא קריטית ומלווה בטקסיות: יציאה למסע, מציאת המקום, חליצת נעליים, ארגון כלי העבודה וצלילה להתבוננות במשך כמה שעות. גם סגירת יום העבודה והחזרה לרכב הן חלק מהטקס. כותרות הספרים וצבעוניות הכריכות מכתיבות את אווירת הציור ואת משמעות החיבור בין העבר וההווה, בין הספר והמרחב הנופי, בין הרגע המשתנה ללא הרף ובין פשטות הכאן והעכשיו של עונות השנה, של השעות ביום, של הטמפרטורה ושל האור. "יש משהו מרפא בטבע. יש משהו מרפא בספר, גם אם הוא קרוע. יש בו קדושה. אני מחברת את הקדושה שקיימת בשניהם. העבודה על ספר נותנת לו רלוונטיות מחודשת. כשאני בטבע אין מחשבות אחרות. רק הציור. רק שאלות כמו מהם הצבעים שאני רואה, מהו השיח או העץ שאני מציירת".

חיימי פניכל

ספרים אנונימיים, מפוסלים באיטונג מוצבים על מדף, מדגישים בצורתם הגולמית את הפער בין האובייקט, המסה המוצקה ובעלת הנפח, ובין מרחבי המחשבה, הרוח, הדמיון והתודעה האין־סופיים החבויים בו. הספר הוא חפץ עתיק, חוצה תרבויות, מגשר בין הממשי למדומיין, בין משקל החומר לאווריריות של רעיון. "הסופרים הראשונים היו פַּסלים", אומר פניכל, "הם היו סַטָּטים, קרמיקאים וחוצבים באבן ובחימר, הם היו אלו שיצרו את התיעודים הכתובים הראשונים. בהמשך היו אלו ציירים וטיפוגרפיים שיצרו את השפה הויזואלית הטקסטואלית. החיבור הזה בין הפַּסל והסופר מאוד מרגש בעיניי. כתיבה וחומר יכולים לכרות ברית שתשרוד את מבחן הזמן, כמו ספרי 'עלילות גילגמש' ששרדו את השריפה בספריית אשורבניפל[9] שבנינווה הודות להיותם לוחות חימר עליהם חרוט הכתוב". רק על ספר אחד במדף חרותים סממנים מזהים – ספר התנ"ך. "אינני אדם מאמין, אבל אני בן המקום, והמקום הזה קשור לספר הזה ולתרבות המקומית".

נעה רז מלמד

"אנציקלופדיה תרבות" יצאה לאור בישראל ב־1962 בהוצאת "מסדה" כגרסה עברית לאנציקלופדיה האיטלקית Conoscere (לדעת), מיזם חדשני לתקופתו, ב־1958, להפצת ידע לצעירים. הרעיון והעיצוב, שהגה העורך ג'ובאני פאברי, התבסס על הוצאה לאור שבועית של מגזינים פופולריים זולים בהדפסה צבעונית, שופעי איורים ריאליסטיים, מתוך כוונה שגיליונותיו ייאספו ויהפכו בהדרגה לאנציקלופדיה שלמה. הגרסה העברית הֶעשירה את התוכן בערכים ייחודיים על יהדות, ארץ־ישראל ותרבות מקומית והקפידה לשמור על האיורים האיטלקיים המקוריים. הגיליונות, שלא היו ערוכים לפי סדר אלפביתי, הציעו מסע אקלקטי בין תחומי דעת. מי שגדלו בישראל בשנות ה־60 וה־70 זוכרים בערגה את "אנציקלופדיה תרבות" בכריכתה הכתומה כמקור לימוד מהימן בתחומים שונים.

נעה רז מלמד יצרה את העבודה "קריעות שקראתי" במהלך החודשים שקדמו לתערוכה. היא מתארת את תהליך העבודה כהתקף בולמוס, כדחף אובססיבי לשבש ולטפל במהותם השורשית של ערכים אנציקלופדיים ואמיתות בסיסיות. העבודה "קריעות שקראתי" היא בבואתה של המציאות הכאוטית העכשווית: קריסת ערכים ומערכות ועיוות וסילוף האמת והכזב. הגיליונות הצבעוניים המקוריים, שהיו כה עליזים ומרעננים בנוף הישראלי בצבעי החאקי באותן השנים, הופכים כעת בקריעתם ובמיקומם המעורבב למופע צורם ודיסהרמוני. הדימויים המרהיבים כמו טובעים בים של מילים חסרות פשר, כמו מופע הריסות של חורבן התרבות.

שיר שבדרון

שיר שבדרון רושם ומצייר פורטרטים אינטימיים זה שנים. הסדרה שבתערוכה נוצרה במהלך 2025 על גבי מילון שהיה בביתו והפך למצע העבודות. שבדרון פותח את המילון באקראי, רושם על אחד הדפים, חותם ומתארך, ורק לאחר שסיים הוא מגלה את המילים שנותרו ברקע. הרישום בטושים על דפיו הדקים של המילון יוצר עקבות ושכפולים. שבדרון חוזר שוב ושוב על אותם המוטיבים – ציור מתוך ציור, פורטרט אחרי פורטרט, כד ועוד כד, ספלים, ספות, ארונות־ספרים וכיסאות. הוא עובד באינטנסיביות, מתחיל באקריליק, עובר לצבעי־שמן, מגדיל פריימים קטנים לציורים גדולים, משחק ומרכיב מחדש את דמותו ואת דימויי הבית והעולם שסביבו. החזרתיות מייצרת מארג מתמשך של זהות וזיכרון, מבט מתמיד בעצמי ההולך ומשתנה, שיבה נצחית למקום מוכר אבל בכל פעם ממקום חדש לגמרי.

כך, בתוך בבואתו מסתתר הילד שהיה, כמו גם קווי דמותו של אביו. הבעת פניו, הנראית נוקשה, כאובה או עצובה ברישומים, מתארת פעולת רישום, ריכוז בהתבוננות.

ליאור שור

תפקידן של מילים והגדרות הוא מתן משמעות ברורה, אולם נדמה כי בשבר שחוֹוה החברה הישראלית ולנוכח עודף המלל, השיח והפרשנות, הפכו אלה לבלתי אפקטיביות. מתוך תחושת חורבן מתמשך וקושי לדמיין יצירה של דבר־מה בעל תוקף, חוזרת שור אל הספרות העיונית המודרניסטית, אל מגדירים, לקסיקונים ואנציקלופדיות שחוברו בעידן האמת.[10] היא מוצאת נחמה ועוגן בחומריותם הישנה, בשפתם האנכרוניסטית לעיתים, בריחם ובמגעם.

המיניאטורות הטקסטואליות של שור נוצרות ברצף פעולות עדין בטכניקת שירת מחיקה (Blackout poetry).[11] היא גוזרת, מוחקת ומבליטה בעת ובעונה אחת, מבודדת מילים ועורכת אותן מתוך היגיון אישי. היא מחפשת אחר פשר, חושפת את הממד הנפשי והפואטי של יסודות התרבות. מהלך זה מאפשר לתחבירים פואטיים, כמעט מכושפים, להגיח מתוך טקסט קיים, להמיר עודפות ריקה בתהליך של זיקוק: "כאילו נתעבו הכוחות הגלומים בחומר, ונחשפו האפשרויות הגדולות", מתוך שירת מחיקה, ליאור שור, 2025

מיכל שכנאי

קולאז' הווידאו "ההבטחה" הוא תלכיד מהפנט המעמת את ההווה עם רוחות הרפאים של העבר. בבסיס העבודה מופיע חומר שליקטה מיכל שכנאי מתוך "האנציקלופדיה של ישראל בתמונות" (מארז אלבומים מפואר, 1950, עורך: יהושע קלינוב, בהוצאת 'לעם'). המארז, שעם השנים הפך לפריט אספנות, כולל שמונה אלבומי תמונות, והוא מייצג את הממשק שבין צילום להבניית זיכרון קולקטיבי לאומי. אלבומיו כרוכים בכריכות העור וריקועי הנחושת בסגנון בצלאל וערוכים על פי נושאים, כמו תקומת ישראל; מועדים; ילדי ישראל; המאבק על ירושלים ועוד. התצלומים המופיעים באלבומים צולמו בידי מיטב הצלמים של תקופת קום המדינה, בהם: בנו רותנברג, בוריס כרמי, זולטן קלוגר, אברהם סוסקין ועוד.

בטכניקות של קולאז', וידאו ואנימציה משולבות בטכנולוגיות AI שותלת שכנאי בדפי האלבומים דימויים וסרטי וידאו ממקורות שונים. כל אלו מלווים בפסקול מטופל של טקסי פולחן וחג אוניברסליים ומקומיים. "ההבטחה" הוא פרק משמעותי במהלך יצירתה רב־השנים העוסקת ונוגעת בזיכרון הישראלי הקולקטיבי. בהומור עדין היא משבשת, בוחנת ומורידה אל קרקע המציאות את האתוס הישראלי, מזקקת רסיסים של מיתוס, ומתבוננת בפערים שבין העבר וההווה, בין החלומות ודיסטופיית המציאות, בין החזון והשקר, הבנייה וההרס, החגיגה והאסון, הקדושה והחולין. שכנאי מחזיקה בתקווה ואיננה מבכה את המקום, ואף על פי כן, את "ההבטחה" אופף ניחוח של קינה וצביטה בלב.

שאלה: האם במקום שנותר פה, להכניס שמות מפתח של הרוחות של הדמויות שבתערוכה?

זה המון עבודה ואני מתלבטת אם זה מגניב או מיותר.

אשמח לדעתך

יש בזה באמת משהו מגניב, שהופך את הטקסט לחלק מתערוכה ולא "על התערוכה" נותן לרוחות הרפאים מקום שווה לעבודות, לאמנים, לאוצרת.

זה יהיה נחמד מאוד הטשטוש תחומים הזה בהקשר של "הספר" וכל המפתחות שלו, ואז אפשר להוריד קצת דמויות מהמשפט שבטקסט...

כן, זה יהיה ממש ממש חמוד, אני מנסה לחשוב אם זה לא יומרני קצת, אבל נראה לי שזה יותר מעלה חיוך פשוט. יצירתי. [1] [2]

[1] בהקדמה של האנציקלופדיה העברית נכתב: "אמונתנו חזקה כי נגשים את שאיפתנו לתת תוכן מעולה בכלי מפואר ולהוסיף ולשכלל מכרך לכרך, וכי נסיים במשך חמש או שש שנים את הוצאת כל ט"ז הכרכים". בפועל נמשכה הכתיבה למעלה מ־30 שנה, ורק ב1980 נשלמה הוצאתה לאור. מנויים על האנציקלופדיה שהמתינו שנים ארוכות להשלמתה, יצאו במחאה וב־1964 אף הגיעו לדיון בבית משפט. ב1971 פוטר ישעיהו ליבוביץ מעריכת האנציקלופדיה משום שההוצאה רצתה לזרז את קצב הוצאת הכרכים, בניגוד לעמדתו שהדבר יפגע באיכות. עם השלמתה מנתה האנציקלופדיה 32 כרכים, ובתוכם שלושים אלף ערכים.

[2] זיגמונד פרויד, "הפרעת זיכרון על האקרופוליס" ]מכתב לרומן רולן לרגל יום הולדתו השבעים[. תרבות, דת ויהדות: כתבים נבחרים, ה', מגרמנית: נועה קול ורחל בר־חיים, תל אביב: רסלינג, ,2008 עמ' 228–.237

[3] לב כנען, ו. (2019). קינה על האקרופוליס: פרויד והעולם העתיק. מכאן, י"ט, עמוד 84

[4] רעם, 1960, הטקסט "מתוך זמירות של חרקולים" מופיע גם במבחר שיריו - סידרת זוטא. הקיבוץ המאוחד. הספריה החדשה, בעריכת הלית ישורון

[5] George Grosz ג'ורג' גרוס, 26.7.1893 - 06.07.1959, נודע בזכות ציוריו הפוליטיים: צייר וקריקטוריסט גרמני בימי רפובליקת ויימאר, חבר בתנועת הדאדא וחבר המפלגה הקומוניסטית. בסמוך לעלייתה של המפלגה הנאצית לשלטון בגרמניה, עזב לארצות הברית. בשנת 1959 חזר לברלין ונפטר בה זמן קצר לאחר מכן.

[6] באיטלקית, Capitello אלמנטים צבעוניים בקצותיו של ספר. כיום אלו סרטים צבעוניים שמודבקים לרוב בשני צבעים.

[7] המונח ארטיביזם ממזג בין המילים Art (אמנות) ו-Activism (אקטיביזם) ומתאפיין בשפה ישירה, ביקורתית, לעיתים הומוריסטית או פרובוקטיבית. מטרות זרם אמנותי זה הן יצירת חוויה רגשית וחושית להנעת הצופה לחשוב ולפעול במרחב החברתי, הפוליטי או הסביבתי. ארטיביזם שואף לשוויוניות בין יצירה אמנותית ובין פעולה חברתית-פוליטית - לא רק יצירת אמנות יפה או ביטוי אישי, אלא גם שינוי תודעה והשפעה על ציבור.

[8] משנה, מסכת אבות פרק ג', משנה י"ז:"רבי אלעזר בן עזריה אומר: אם אין תורה, אין דרך ארץ. אם אין דרך ארץ, אין תורה. אם אין חכמה, אין יראה. אם אין יראה, אין חכמה. אם אין בינה, אין דעת. אם אין דעת, אין בינה. אם אין קמח, אין תורה. אם אין תורה, אין קמח".

[9] הספרייה המלכותית על שם אשורבניפל, מלכהּ האחרון של האימפריה הנאו־אשורית, היא אוסף של אלפי לוחות ושברי חרס המכילים טקסטים מגוונים בכתב יתדות ומתוארכים למאה ה־7 לפנה"ס. הכתבים הראשונים התגלו ב־1849 בארמון סנחריב מלך אשור, בחפירות נינווה (כיום תל קויונגיק) בצפון מסופוטמיה, באזור הנמצא בשטח עיראק, על ידי הארכיאולוג הבריטי אוסטן הנרי לייארד וצוותו. רוב הלוחות נלקחו לארכיון המוזיאון הבריטי בלונדון.

[10] עידן המודרניזם מתאפיין באמונה באמת אחת ואבסולוטית. זאת, אל מול הפוסט־אמת שנחווית כיום כמשבר ונקודת קיצון של הפוסט מודרני.

[11] שירת מחיקה (Blackout poetry) היא טכניקה חזותית ליצירת שירה על ידי השחרת או מחיקת מילים מטקסט קיים (רדי-מייד) וסימון הפעולה על הדף כמו שירה.

התחלתי לעשות רשימה וזה אין סופי. כמות הספרים שיש בתערוכה היא ענקית: הסופרים, הדמויות, העורכים, הצלמים ועוד ועוד. אני משאירה את זה פתוח, אולי אכניס את זה בהמשך.

אז אם יש המון המון אולי כדאי לוותר, כי אם זה over, זה עלול להיות קצת תמוהה ולאבד מהעוקץ או לבלבל. או שזה דווקא הרעיון, לבלבל קצת. בקיצור, גם אני לא יודעת להחליט.

The Intellectus Movement, Exhibition No. 51, The Final Exhibition

Tamar Branitzky, Yair Barak, Haimi Fenichel, Hadar Gad, Nava Harel-Shoshani, Omri Harmelin, Ruthi Helbitz Cohen, Jonathan Hirschfeld, Dana Manor Cohen, Noa Raz Melamed, Gabby Salzman, Michal Shachnai, Lior Shor, Shir Shvadron, Drora Weizman, Roni Yoffe, Dalia Zerachia

Curator: Rotem Ritov

The final exhibition carries a heavier load. Like an afterword or a farewell letter, it bears a latent responsibility to conclude. It is the weight of summary, embedded with messages and insights with significance and hope vis à vis what has been, what will be, and most of all the void that will remain.

I worked on this exhibition slower than usual, as if I was delaying the end. At the same time, a book was coming together to summarize the gallery’s activity since its foundation. Its launch is planned during the exhibition.

The book’s preparatory work inspired the exhibition’s concept! A book marks a complete continuum: beginning, middle, end. It is a special object that supersedes its own materiality, volume, or function. It encompasses the riches of the spirit, the intellect, the imagination, as well as layers of culture. Its impact remains planted within our souls far beyond its physical presence.

And now, we stand on the threshold of one of the greatest revolutions humankind has ever known. Little more than a century ago, in the early twentieth century, most of the world’s citizens did not know how to read or write, and its female citizens were even prohibited from knowing. Since then, illiteracy has dropped continuously and has almost been obliterated. In the not-too-distant past, the sources of knowledge were encyclopedias, literature, dictionaries, and handbooks. Books were written and edited, printed, and bound, with great care and meticulousness, and were even bestowed with pomp and ceremony as gifts at important life events. Books symbolized status, education, intellect, and faith in the written word. Yet, the internet revolution has transformed the world order, and shelves once crowded with the heavy volumes of the Encyclopedia Hebraica[1] now house plasma screens. And within the digital revolution, artificial intelligence opens the door to knowledge and creativity of an intensity and depth never known before, changing how we think and create.

But along with creative freedom and the capacity to connect with unending information comes great uncertainty. The truth has become slippery, fluid, relative, and humanity faces a new challenge: to safeguard the truth, distinguish between fabrication and fact, reliable or fallacious source. Intelligence is fighting for its footing.

In the exhibition The Intellectus Movement, many spirits are present: from Ruth the Moabite, Molière, George Grosz, Yeshayahu Leibowitz, and Virginia Woolf to Jewish artists who perished in the Holocaust and generations of bookmakers whose names will never be known. Their perpetuity derives from stories passed from generation to generation, from the written word, from the expansion of knowledge and the values of scholarship, creativity, and research. These spirits emerge from the artworks on display, connecting the contemporary generation of artists to the multigenerational continuum of the Intellectus Movement. It is important to appreciate the opportunity to be a part, even a modest part, of the evolution of human knowledge.

Yair Barak

Yair Barak’s works in this exhibition are part of a sub-series in the body of work Regarding History. They were created in 2008 within a master’s program at Bard College, New York, and have been exhibited in various iterations since. There, in New York, as a guest in another culture, in another country, working in an alien landscape, he sought to continue to delve deeper into the issues of identity, foreignness, and localness, which he had previously addressed in the Israeli sphere.

Within his work on Regarding History, Barak was exposed in the college’s impressive libraries to the rich collections of natural history books, hand bound in canvas and linen, according to mid-twentieth century book industry practice. Barak: “I fell in love with the materiality and how the books narrated history. I didn’t pay attention to the books’ content, rather to how things were presented, the symbols and typography. What interested me was thinking about aesthetics on one hand, and how history is told, on the other hand.” In his works, the books function as an archetypical representation of the infrastructure of Western culture, and as an abstract idea, a concept. The books are positioned within compositions that reference the fundamental concepts of Classical architecture (gate, staircase), contemplating the text as a structure and building block of Western culture. The works were created using the packshot technique (photography against a clean, white background), but instead of camera and studio, the sophisticated scanner in the college’s digital lab became his workspace.

Gabby Salzman and Tamar Branitzky

The working process of Gabby Salzman and Tamar Branitzky is founded on full dialogue and collaboration at all stages of creation. In their works, they incorporate object (book), material (textile), text, and graphic image, reverting to manual gestures from traditional crafts: silkscreen and sewing machine. Their works have a wealth of dimensions and references, personal memories, and nostalgia. The soundtrack of their youth is sewn on their childhood library from the time when they were schoolchildren, right before it will disappear. “My father was a tour guide, and his book collection is a childhood treasure. Carta Publishing’s iconic atlas was a huge part of my childhood. When my father shared his intention to dispose of his library and the atlas, I felt like I had to save them and preserve something from that period. Handling the old books keeps them in the realm of the living, enchanted, and romantic,” describes Salzman. And Branitzky adds, “the act of sewing the letters makes the passing memory palpable and clear. The black thread is transformed from a mechanism for fastening into a tool for illustration, and the longing becomes contemporary material.” The works in the exhibition are just a small part of their joint work. The book always serves as their work’s support, and is conceived in their works as a nostalgic childhood object which garners new life, to bring forth childhood experiences, optimism, and wonder at the moment.

Haimi Fenichel

Anonymous tomes on a shelf, sculpted in autoclaved aerated concrete, emphasize in their raw form the gap between object, solid voluminous mass, and the infinite expanses of thought, intellect, imagination, and consciousness concealed within them. The book is an ancient, intercultural object which bridges between real and imagined, between the weight of the material and the weightlessness of the idea. “The first authors were sculptors,” states Fenichel, “they were stonemasons, ceramists, and they carved in stone and clay. They are the ones who created the first written documentation. Later, it was the painters and typographers who created the visual-textual language. In my view, this link between sculptor and author is very exciting. Writing and material can create an alliance capable of standing the test of time, like the Epic of Gilgamesh which survived the fire in the Ashurbanipal Library[2] in Nineveh, thanks to the fact that the tales were etched on clay panels.” Identifying marks are carved into only one book on the shelf – the bible. “I am not a believer, but I do belong to this place, and this place is connected to that book and the local culture.”

Hadar Gad

In 2019, Darsie Alexander, Chief Curator of the Jewish Museum in New York, invited Hadar Gad to participate in a project on the Nazi looting of Jewish art. During Gad’s research in various archives, she found the names of many Jewish artists who were deported from Paris to Auschwitz. “Although these were artists from different places in Europe, I discovered that their deportation numbers were consecutive. Almost all of them were deported together in the train’s cars from Paris, apparently after they had fled there. I felt a deep need to document, to create some kind of monument, and to memorialize such a broad, complete stratum of culture that was wiped out,” states Hadar Gad.

The act of commemoration entered the books’ illustrations – the artists’ names are recorded on the illustrated books’ spines: “It’s like a Trojan painting. Each name is latent yet present, and the viewer uncovers the story through the names.” The name of the series is Disturbance of Memory, taken from Sigmund Freud’s essay “A Disturbance of Memory on the Acropolis,”[3] written as a letter to his friend, French author Romain Rolland, during a visit to Athens. In an article on Freud, Vered Lev Kenaan writes that in this letter, which he wrote in the last days of his life in 1936, “two different yet intertwined issues arise, which share a common denominator that can be described as a link to Freud’s cultural and intellectual origins […] his Jewish identity on one hand […] and the Classical education he received in secondary school on the other hand, resulting in the image of a life that involves two-facedness, duality, and self-contradiction […]. Freud’s return to the two foundational sources of his complex identity focuses on the connection between the figure of his father, Jacob Freud, and the sublime image which represents the ancient world, the Acropolis. The two symbols, the father and the mountain, as representations of a world that was and is no longer […] echo for him a sense of loss which elicits a desire for introspection […] Freud’s thoughts about his dead father merge with thoughts about a world that was always like a home for him, although it was not really his, but rather a longed-for birthplace.”[4]

Another work by Hadar Gad is a drawing of Cyclamen flowers spanning across pages six and seven of Avoth Yeshurun’s book “Thunder”[5]; According to Gad, daily drawing in books and journals focuses her and puts the creative process in motion.

Nava Harel-Shoshani

In the work People of the Book 2, Nava Harel-Shoshani welds together two familiar symbols: one is the image of books on a shelf, which represents Judaism’s deep ties to the book, study, the written word, and discourse; the second is the image of the Separation Fence, which represents, in the harshest way, the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, and its physical expression in the geographical space. Casting concrete on encyclopedia volumes transforms them from spaces of knowledge to monuments of a disputed place. As background for the work, Harel-Shoshani expresses her stance: “We have been transformed from a persecuted people to the persecutors.”

Harel-Shoshani acts in the realm of Artivism,[6] and her artwork is dedicated to articulating a response to the reality of current events in Israel, conveying political protest, and raising society’s awareness of various aspects of the occupation and the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

Omri Harmelin

The work The Truth’s Last Breath belongs to a series of realistic sculptures of books and bookshelves Omri Harmelin created during the last year. The series addresses truth’s place and status in an unstable world. Each object-book in the series conveys a condensed idea about the verbal content concealed between the pages of the book, which cannot be turned. Together, the works constitute a sculptural archive of contemplations on the essence of truth. The choice of the book, and the decision to sculpt it in such a realistic manner, convey a desire to decipher the meaning of the book, which traditionally symbolizes the source of certified truth, life wisdom, and absolute value, particularly in today’s times, when the truth is losing clarity from day to day. In the age of fake news and artificial intelligence, the questions what is real and who speaks the truth are becoming essential. The work’s name expresses the tension between absolute truth and individual interpretation, between reliable information and fabricated reality, between fact and a vague representation of a fleeting narrative.

Ruthi Helbitz Cohen

In the installation Book of Ruth, Ruthi Helbitz Cohen approaches the biblical story from a personal, intimate perspective. She deconstructs the biblical text to reread it. She selects key phrases, deletes, interprets, and connects, transforming the book into a personal, female diary. In the video work at the center of the installation, a scroll of the Book of Ruth with drawings is revealed. Slowly scrolling through it, the yad, or ritual pointer, directs to the verses the artist has created, accompanied by two women singing, two voices: The first is the voice of Hila Cohen Chesla, a teacher of biblical cantillation; and the second is that of Naomi, the artist’s young daughter, who repeats after her teacher. This subtle, poetic, and vocal tribute creates an act of intergenerational transmission, which positions the relations between mother, daughter, and teacher along a spectrum of female voices which demand to be heard in a man’s world.

Like an audience, large-scale androgynous figures stand on hanging paintings. It is unclear whether they are wounded or animalistic. They bear witness to the act of chanting. The fragility of the figures in the paintings represents the female body’s power in the face of tradition, underlining the trajectory from vulnerability to resolve. Through painting, drawing, video, and sound, Helbitz Cohen blurs the boundaries between sacred and profane, between trivial, quotidian material and ancient, canonical text. She rebuilds a female ceremonial space. This is a space where the biblical story becomes a tool for writing about love and pain, parting ways and continuity, where the female body and voice are newly etched in history.

Jonathan Hirschfeld

“I gave birth* to three minor series, and their offshoots, because of the current situation. My whole life as a painter I have had reservations about political art. I have always steered my art towards more metaphysical, eternal, and universal terrain. I thought of myself as an artist who acts, not in reaction to reality, but from my own personal wellsprings. But the enormity of the October 7 tragedy, Israel’s spiritual and moral downfall, the endless war, and the dismemberment of Israeli democracy, all found their way into the studio in the end. I tried to maintain my own painterly act, abstraction, Israeli Modernism, and the direct glance, to bring politics as the background, as the subconscious buried beneath. It’s all there in George Grosz’s[7] booklet of political etchings: bestiality, fascism, war – all of it. I placed my usual Hirschfeld gestures over them: here and there an Israeli flag came out, here and there lyrics from Jerusalem of Gold. Finally, I purchased a religious book, and repeated the same acts: Because the truth is, beneath the political subconscious, is the religious subconscious.” Jonathan Hirschfeld, 2025

*I gave birth, because I was impregnated, politics fucked me.

Dana Manor Cohen

Dana Manor Cohen’s studio is crowded with old books, placed in piles instead of on shelves. She paints on book covers selected carefully, out of respect for the heritage they embody. “These books were once important to someone, and thought and work were put into every detail. Finding an old book is like finding a treasure. It holds a secret. Old books are a bridge between past and present. They carry memories, especially books that are old, torn, at times covered in mold and sometimes bearing dedications.” Manor Cohen describes the excitement of turning them into a painting support. She paints on the book covers in plein air, in places she likes, lives in, or visits. The act of painting the chosen “place” is critical and replete with ceremony: embarking on the journey, finding the spot, taking her shoes off, setting up work tools, and diving into observation for several hours. Even finishing the workday and returning to the car are part of the ceremony. The book titles and colors on the covers dictate the painting’s vibe and the meaning of the connection between past and present, between book and landscape, between the moment that changes incessantly and the simplicity of the here and now in the seasons of the year, the time of day, the temperature, and the light. “There is something therapeutic about nature. There is something therapeutic about books, even if they are torn. There is something sacred about them. I merge the sanctity present in both. Working on the book grants it a new relevance. When I am in nature there are no other thoughts. Just painting. Just questions like what are the colors I see, what is the bush or tree I am painting?”

Noa Raz Melamed

The Tarbut Encyclopedia (Culture Encyclopedia) was published in Israel in 1962 by the Massada Publishing House. It was the Hebrew version of the Italian encyclopedia Conoscere (to know), a 1958 initiative that was groundbreaking for its time, to spread knowledge among youth. The concept and design, conceived by its editor Giovanni Fabbri, was based on the weekly release of affordable popular magazines, in color print, teeming with realistic illustrations. The idea was to collect the issues, which would gradually become a complete encyclopedia. The Hebrew version enriched the content by adding unique entries on Judaism, the Land of Israel, and local culture, while making sure to maintain the original Italian illustrations. The issues, which were not prepared in alphabetical order, provided an eclectic journey between areas of knowledge. People raised in Israel in the sixties and seventies nostalgically recall the Tarbut Encyclopedia, with its orange cover, as a reliable source to learn about different fields.

Noa Raz Melamed created the work Cuttings I Have Read during the months leading up to the exhibition. She describes the working process as a hunger attack, an obsessive urge to twist and tamper with the very essence of encyclopedia entries and basic truths. The work Cuttings I Have Read reflects the chaotic contemporary reality: The erosion of values and systems and distortion and perversion of truth, and falsehood. The original colorful issues, which were so cheerful and refreshing in the khaki-colored Israeli landscape of those years, are now transformed, in their torn state and discombobulated positioning, into a grating, disharmonious sight. It is as if the spectacular images are drowning in a sea of meaningless words, like the sight of ruins following the destruction of culture.

Michal Shachnai

The video collage The Promise is a hypnotizing conglomeration which confronts the present with the ghosts of the past. At the base of the work is material Michal Shachnai gathered from the Encyclopedia of Israel in Pictures (a lavish album set from 1950, edited by Yehoshua Kalinov, published by La’am). The set, which has become a collector’s item over the years, comprises eight albums of photos, and represents the meeting point between photography and constructing a national collective memory. Its albums are bound in leather with copper flattening in the Bezalel style. It is arranged according to topics, such as: the rebirth of Israel’s homeland, holidays, Israel’s children, the battle for Jerusalem, and more. The photographs appearing in the albums were taken by the best photographers of the period, the years around Israel’s independence, among them: Beno Rothenberg, Boris Carmi, Zoltan Kluger, Avraham Soskin, and more.

Integrating techniques of collage, video and animation using AI technology, Shachnai plants in the album’s pages images and videos from various sources. These are accompanied by a manipulated soundtrack of local and universal ritual and holiday ceremonies. The Promise is an important chapter in her long creative career, which addresses and touches on Israeli collective memory. With subtle humor, she distorts and tests the Israeli ethos, bringing it back down to earth. She distills shards of myth and observes gaps between past and present, dreams and the dystopia of reality, vision and falsehood, building and destruction, celebration and tragedy, sacred and profane. Shachnai maintains hope and refrains from mourning the place. Yet despite this, an aura of lamentation and heartache pervades The Promise.

Lior Shor

The role of words and definitions is to provide clear meaning, yet it seems they have been rendered ineffective within the crisis Israeli society is undergoing and in the face of an excess of verbiage, discourse, and commentary. Out of a sense of continuous destruction and trouble imagining producing anything with the force of validity, Shor returns to modernist scientific literature, to the handbooks, lexicons, and encyclopedias composed during the age of truth.[8] She finds comfort and footing in their old-school materiality, their sometimes anachronistic language, their smell and feel.

Shor’s textual miniatures are produced in a subtle sequence of acts using the blackout poetry method.[9] She cuts, erases, and emphasizes all at once, singling out words and editing them according to her own logic. She searches for significance, exposing the mental and poetic dimensions of the fundamentals of culture. This process allows poetic, almost enchanted, compositions to emerge from an existing text, converting an empty excess in a process of distilling: “It is as if the powers inherent in the material have been augmented, revealing the great possibilities,” from Lior Shor’s blackout poetry, 2025.

Shir Shvadron

Shir Shvadron has been drawing and painting intimate portraits for years. The series in the exhibition was created during 2025 on a dictionary he had in his home, which became a support for the works. Shvadron opens the dictionary at random, draws on one of the pages, signs and dates the work. It is only after he has finished that he discovers the words remaining in the background. Drawing with markers on the dictionary’s thin pages leaves traces and doubles of images. Shvadron returns to the same motifs over and over: a painting within a painting, portrait after portrait, vessel after vessel, mugs, sofas, bookcases, and chairs. He works intensively, starts with acrylic, moves to oils, enlarges small frames into large-scale paintings, plays with and recomposes his own image as well as images of the home and world around him. The repetition produces a continuous fabric of identity and memory, a persistent observation of the ever-changing self, an infinite return to a familiar place, yet each time coming from a new place entirely.

Thus, within his reflection hides the child who was, as well as the outlines of his father’s image. His facial expression – which in the drawings appears harsh, pained, or sad – depicts the act of drawing, concentrating on observation.

Drora Weizman

“Take a book and slice it with knife and fork, close your eyes and eat it: the margins of pages; title; stamp; texture of the text; layers of binding, with cardboard and gauze and fiber for support; and a crumbling fabric bookmark. Take a book and rescue it from its past, future, and reincarnation, from oblivion, from the trash heap behind the genizah[10].”

Drora Weizman, May 2013

Drora Weizman creates in the dynamic space between decomposition and preservation, between farewell ceremony and act of creation. In her hands, books, the bearers of knowledge, discourse, and culture, are transformed into raw material charged with individual and collective memory. In an intimate, manual, process, she breaks them down into parts: spine, binding, capitello[11], margins of pages, sewing thread, stains, and textures. She saves them, sorts them, and puts them back together in sculptural structures and installations. Her works beckon a slow glance at the materiality of time, the remnants of hidden worlds. Weizman contemplates them as messengers and angels, the keepers of a lost message, and brings them back to life, but to a different one. She achieves this through meticulous gestures of arranging, pasting, joining, and positioning. She calls her workspace “the suction pump” – a space that receives, absorbs, and sorts: “The work is executed in the kitchen and living room, on tables and the rug, at all hours of the day with the television on and the news blazing,” wrote Weizman in 2021.

The order of her working process is as follows:

I. First, external cleansing, then leafing through the book and studying it, saving inspirational words and images.

II. The next stage is internal cleansing: removing all content. There is significance to how the pages are torn: one by one, in groups, in a downwards or upwards motion, slowly or quickly. Each act impacts the appearance attained. Naturally, there is a difference between books fastened by glue, staples, or sewing thread.

III. After cleansing, the book’s spine is revealed, and it is released from its binding, like fileting a fish until its skeleton appears. Each spine has its own internal distribution, according to the threads and seams that hold the pages, and how they are removed. Sometimes Weizman writes the book’s title in pencil before its identity disappears entirely.

IV. Treatment of the capitello: If the fabric strips (that serve to reinforce and adorn the books’ edges, adjacent to the spines) are attached well, they remain. If not, they are cleansed separately, stray threads are cut away, and they are collected in a box.

V. Treatment of the back of the book: When the front and back binding are dismantled, the back of the book, and the words on it, remain. All peelings are removed, rips are mended, and the torn-away segment leaves the choice whether to treat the binding’s external side (which is usually red) which bears words etched in the title, and has a certain uniqueness, a special defect or texture. The choice to treat the binding’s internal side leads to continued acts of excavation and archaeology in the cardboard layers.

VI. Finally, reconstruction: dog-eared and eaten alongside the posh and new, the overused with the rare, faraway worlds from lands and peoples that preceded the era of screens, the fathers of education and the mothers of culture, memories from our parents’ homes and our homeland’s rebirth, remembrance in a velvet binding, wars and arts that are now easily accessible, at the highest level, on the internet.

In the exhibitionThe Intellectus Movement, Weizman brings forth a new vision – a library.

“Sometimes it starts with words, you just have to reveal them to someone and take it from there,” Drora Weizman, 2025

Roni Yoffe

The classical painting tradition which Roni Yoffe studied in Florence, serves her as a tool for observing Israel. The still life representations in her paintings are objects that symbolize layers of local culture, through which she examines the relations between matter and spirit, order and chaos. The starting point for her two paintings in the exhibition is the Mishnaic pronouncement, “Where there is no flour, there is no Torah.”[12] This utterance addresses the interconnection between the material, existential needs, and intellectual life. Yoffe expands the saying beyond its traditional realm: flour with strict kashrut certification versus flour imported from Italy; the Jewish bible versus a pile of books on various fields of knowledge: philosophy, prose, research, evolution, classics, a flora handbook, poetry, children, and an atlas. The cultural gap between the religious and secular worlds is also reflected symbolically in the composition: the clean, clear, conservative, and symmetrical one versus the disorganized and diverse one that contains a selection of cultural and intellectual fields. A yellow bookmark hides between the pages of the secular space, echoing the battle to bring the hostages home, transforming the painting into an arena where history, culture, and current events are intertwined.

Dalia Zerachia

Many of Dalia Zerachia’s works are based on memory-bearing objects. The spirit and past embedded within them serve as outlets for her artistic response and for a journey to expose the history concealed within them.

The “book” artworks displayed in the exhibition are just a small part of a larger body of work Zerachia has been working on for about two years, since Tami Suez placed in her hands a large book collection, part of the private collection of Uzi Agassi, collector, historian, art critic, art printer, publisher and founder of the Even Hoshen publishing house, and editor of the literary periodical Shvu. “I picked up the books,” states Zerachia, “and immediately a flood of ideas began to surface. I became obsessed and I started to collect books, even from the street.”

The body of works “book” is a tribute to the art of bookmaking and the tradition of the work of craftspeople, binders, and printers. The development of technological printing, and the accessibility of information online, have changed how we create and consume culture. Traditional practices have been abandoned and have disappeared, replaced by cheap, readily-available, and quick production. The book’s status as an object and agent of culture has dissipated, its sphere occupied by databases and digital information, changing the face of culture. Zerachia seeks to preserve the past, memory, and history.

[1] The introduction to the Encyclopedia Hebraica states: “We have great confidence that we will fulfill our aspirations to infuse this outstanding vehicle with superb content, getting better and better with every volume, and conclude the publication of all 27 volumes within five or six years.” In practice, writing continued for over 30 years, and publication was not completed until 1980. Subscribers who waited long years for the Encyclopedia’s completion held protests, and in 1964 the matter was even brought to court. In 1971, Yeshayahu Leibowitz was dismissed as the editor because the publisher wanted to expedite the release of new volumes, which went against Leibowitz’s stance that this would come at the expense of quality. Upon completion, the Encyclopedia numbered 32 volumes and comprised 30,000 entries.

[2] The national library named for Ashurbanipal, the Neo-Assyrian Empire’s last king, is a collection of thousands of clay panels and shards containing diverse texts in Cuneiform script dating to the seventh century BCE. The first writings were discovered in 1849 in the palace of the Assyrian king Sennacherib, in the Nineveh excavations (known today as Tel Kuyunjik) in northern Mesopotamia, an area located in Iraq, by British archaeologist Austen Henry Layard and his team. Most of the panels were taken to the archive of the British Museum in London.

[3] Sigmund Freud, “A Disturbance of Memory on the Acropolis,” English translation available at: https://web.english.upenn.edu/~cavitch/pdf-library/Freud_Disturbance.pdf

[4]Lev Kenaan,V.(2019), “Lamentation on the Acropolis: Freud and the Ancient World,” Mikan18, p84 (Hebrew)

[5] “Thunder,” 1960 – the text, from “Zmirot Shel Harkolim (Grasshoppers’ Voices/Songs),” also appears in Avoth Yeshurun, Selected Poems, published by Hakibbutz Hameuchad, edited by Helit Yeshurun

[6] The term Artivism is a portmanteau that blends the words art and activism. It is characterized by direct language, criticism, and at times humor and provocation. The objective of this artistic stream is to create an emotional and sensory experience to motivate viewers to think and act in the spheres of social action, politics, or environmentalism. Artivism strives for equality between artmaking and social-political action: not just creating art for beauty or self-expression but to change awareness and influence the public.

[7] George Grosz, July 26, 1893 – July 6, 1959, was known for his political paintings: a German painter and caricaturist during the Weimar Republic, a member of the Dada Movement and the Communist Party. He left for the United States shortly before the Nazi party rose to power. In 1959, he returned to Berlin and died there soon after.

[8] The age of Modernism was characterized by faith in a single absolute truth. This contrasts with the post-truth of today, as a crisis and the pinnacle of Postmodernism.

[9] Blackout poetry is a visual method of creating poetry by blacking out or deleting words from an existing text (readymade) and marking the act on the page as poetry.

[10] (Jewish repository for disposal of sacred texts)

[11] In Italian, the term “capitello” refers to the painted elements on the book’s edges. Today, they are colored strips, normally pasted in two colors.

[12] Mishna, Avot 3:17: “Rabbi Elazar ben Azariah said: Where there is no Torah, there is no right conduct; where there is no right conduct, there is no Torah. Where there is no wisdom, there is no fear of God; where there is no fear of God, there is no wisdom. Where there is no understanding, there is no knowledge; where there is no knowledge, there is no understanding. Where there is no bread, there is no Torah; where there is no Torah, there is no bread.” English translation accessed at: https://www.sefaria.org/Pirkei_Avot.3.17?lang=en&with=Translations&lang2=en